(English version below)

Due occhi sorridenti e gentili si sono chiusi lo scorso 17 Settembre. Gli occhi luminosi e curiosi di una ricercatrice italiana che è stata protagonista e testimone di tutta la storia del CERN. Sono gli occhi di Maria Fidecaro.

Agli inizi degli anni 50, poco più che ventenne, Maria Cervasi finì gli studi di Fisica alla “Sapienza” di Roma, sotto la guida di Carlo Bernardini, per poi lavorare come assistente nello stesso dipartimento, nel prestigioso istituto di Fisica di Enrico Fermi ed Edoardo Amaldi. E proprio lì, e poi nel corso dei loro esperimenti in vetta al Cervino per studiare i raggi cosmici, incontrò il suo futuro sposo, Giuseppe Fidecaro.

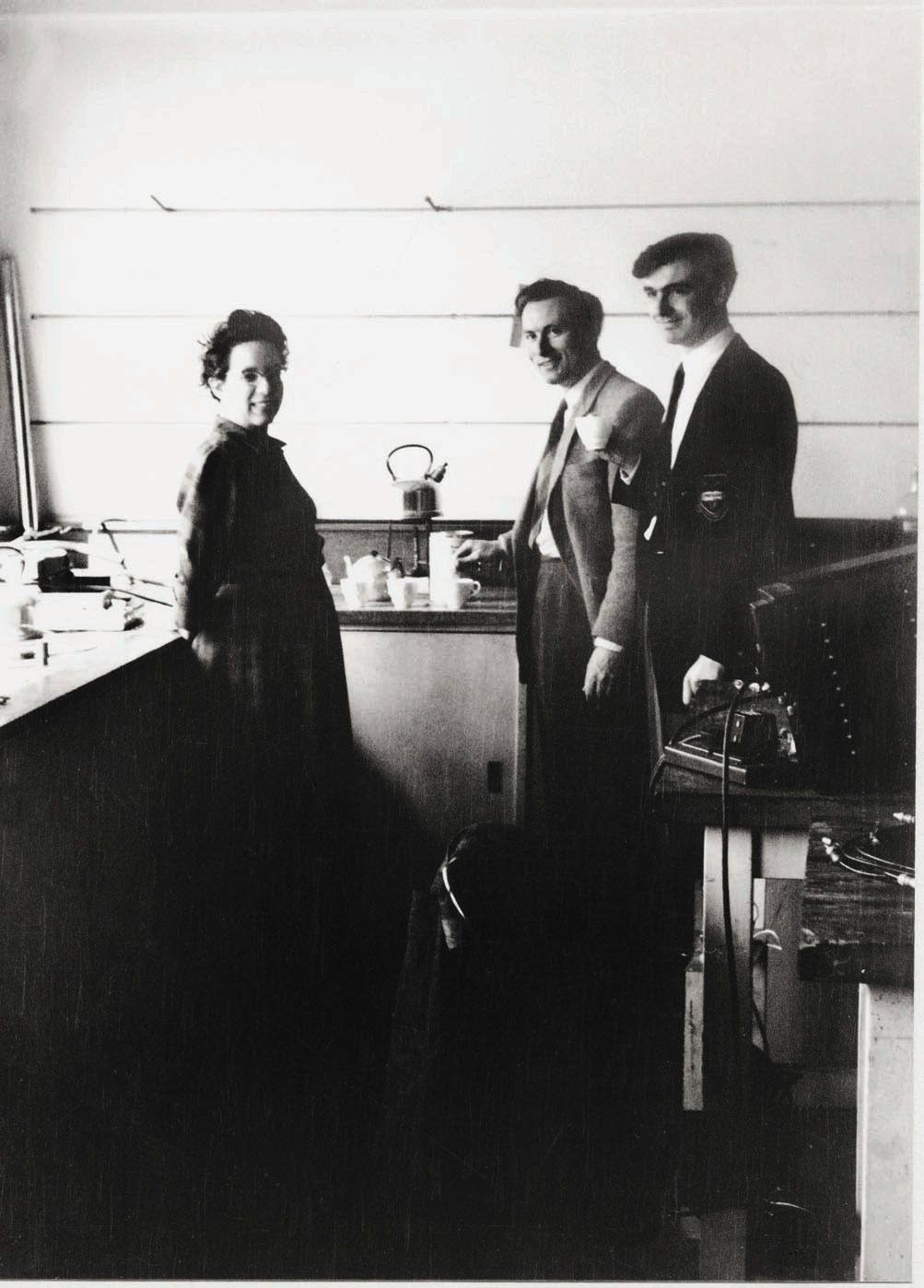

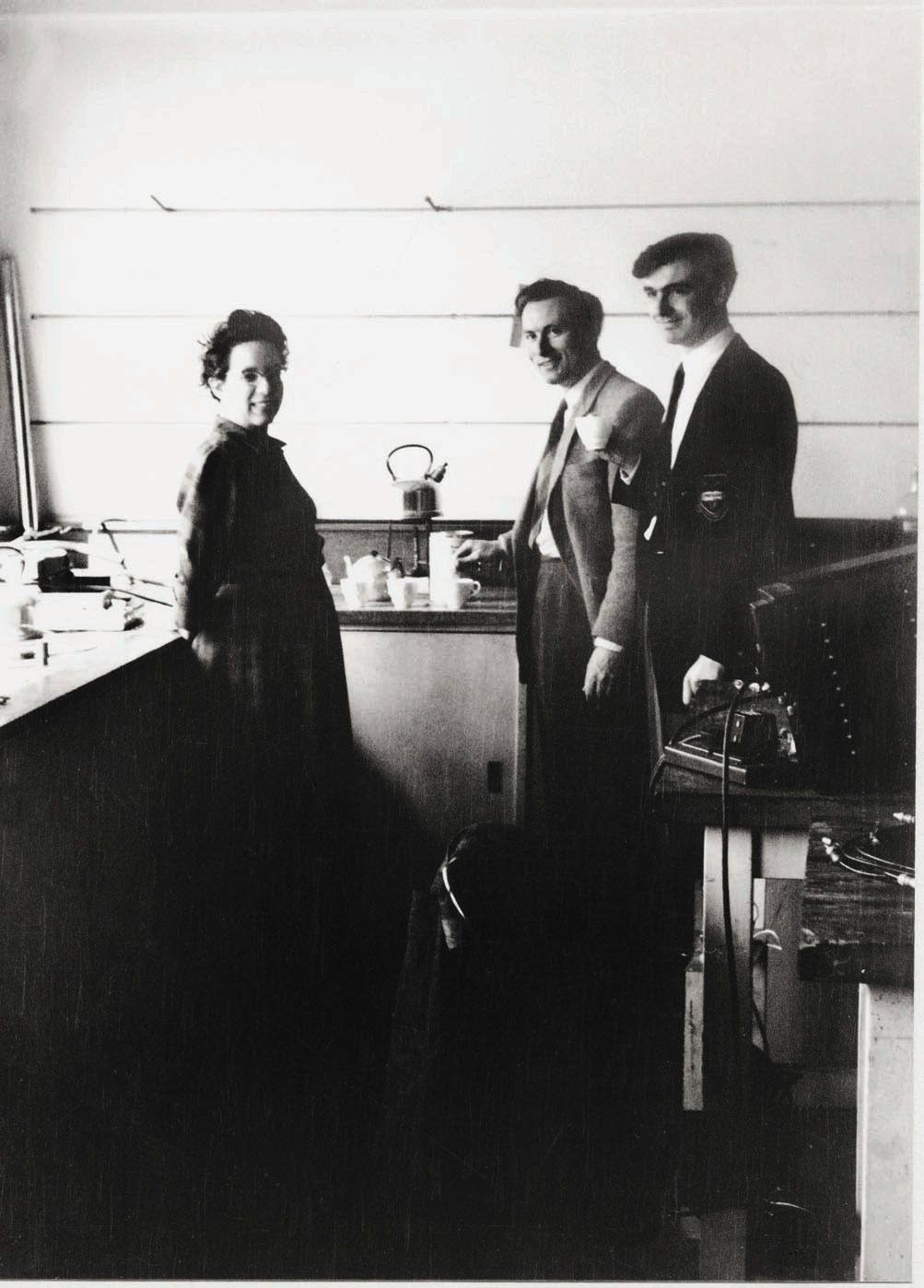

Nel 1954 Maria Cervasi e Giuseppe Fidecaro si spostarono entrambi all’università di Liverpool per continuare i loro studi sul decadimento di particelle instabili con diverse tecniche sperimentali: Giuseppe con una borsa del neonato CERN, Maria con una borsa dell’allora “International Federation of University Women (IFUW)”, oggi “Graduate Women International (GWI)”. C’è una bella foto del 1955 che la ritrae al “Nuclear Physics Research Laboratory” dell’Università di Liverpool insieme a due suoi colleghi, Alec Merrison (poi divenuto sir Alec) e Alan Wetherell.

Nel 1955 i due fidanzati si sposarono, Maria Cervasi divenne Maria Fidecaro, e continuarono il loro lavoro di ricercatori a Liverpool. Ma, arrivata l’estate del 1956, Maria e suo marito Giuseppe lasciarono Liverpool e si trasferirono a Ginevra per raggiungere il primo gruppo di scienziati del CERN. In quel momento, il grande laboratorio europeo, fondato solo due anni prima, era ancora in costruzione. I lavori avanzavano ma nulla era ancora pronto, tanto che gli studi dei primi ricercatori e gli uffici erano ancora ospitati in edifici temporanei: presso l’istituto di fisica di Ginevra e presso Villa Cointrin, come ha spesso ricordato Maria Fidecaro nelle sue interviste.

Maria e Giuseppe lavorarono allo studio e alla costruzione dei primissimi esperimenti del CERN. Come ricordò Giuseppe Fidecaro, in un’intervista del 2014, gli esperimenti dell’epoca erano decisamente più piccoli di quelli moderni, e solo pochissime persone potevano lavorarci. Maria e Giuseppe erano tra queste. E, da allora, han continuato a fare parte della storia del laboratorio.

Anche il gruppo in cui Maria Fidecaro ha iniziato a lavorare al CERN era piccolo, solo tre persone. Lavoravano sul nuovissimo acceleratore di particelle su cui lavorava anche Giuseppe, il “Sincro-Ciclotrone”, e, insieme, progettavano un nuovo sistema per ottenere dei fasci di protoni “polarizzati”: ovvero, dei fasci i cui protoni fossero orientati tutti in una stessa direzione in termini di una loro caratteristica detta “spin”. Nella sua carriera, Maria Fidecaro, lavorò in diversi altri esperimenti al CERN, sui diversi acceleratori del CERN che, negli anni, hanno prima affiancato, e poi rimpiazzato, il Sincro-Ciclotrone: ovvero, il Proto-Sincrotrone (PS) e il Super-Proto-Sincrotrone (SPS). Si interessò, per esempio, allo studio delle interazioni tra nucleoni — ovvero, le particelle che compongono i nuclei degli atomi: protoni e neutroni — e partecipò all'esperimento denominato “WA78”, sull'acceleratore SPS, per la produzione di coppie particella-antiparticella, e all'esperimento CPLEAR, dedicato allo studio della differenza tra materia e antimateria e di come queste possano o meno violare la conservazione di alcune caratteristiche fisiche di base. Per diversi anni Maria Fidecaro guidò il gruppo "CPL" all'interno della divisione "Particle Physics Experiments" del CERN, e contribuì ad avviare altri esperimenti per ulteriori studi sulla violazione delle caratteristiche fisiche di base da parte di alcune particelle, tra cui gli esperimenti “NA48/2” e “NA62”. Negli ultimi anni della sua lunga carriera, inoltre, come ha più volte ricordato lei stessa in diverse occasioni, le piaceva riesaminare i risultati dei suoi precedenti studi, per controllarli e vedere se le fosse sfuggito qualcosa o se qualche altra conclusione potesse essere fatta sulla base dei vecchi dati.

Personalmente, ho conosciuto Maria e Giuseppe Fidecaro nel 2003, quando sono arrivato per la prima volta al CERN, da studente, per preparare la mia tesi di laurea. Purtroppo, non ho mai avuto la fortuna di lavorare con loro in modo diretto; ma in tutti questi anni ci siamo incontrati per i corridoi del CERN; oppure sui tram e autobus che la sera ci riportavano, tutti e tre, verso il centro città; o alle funzioni della chiesa italiana di Ginevra. E in tutti questi anni è stato un piacere incontrarli, salutarli, e ricevere il loro saluto. Un saluto sempre sinceramente cordiale e gioioso, e ogni volta accompagnato dallo sguardo allegro di quegli occhi cosi’ gentili.

Poi, purtroppo l’epidemia di COVID-19 ha interferito anche con la vita del laboratorio e, per molto tempo, non li ho più incontrati. Ma circa un anno fa, in occasione di uno degli incontri celebrativi della storia del CERN, ho avuto la gioia di incontrarli di nuovo. Io quel giorno ero venuto al lavoro in macchina, cosi’, sapendo che Maria e Giuseppe vivevano non lontano da dove io vivo, ho offerto loro un passaggio. È stata una piacevolissima e simpatica passeggiata in automobile: Maria si era seduta davanti e, scoperte le nostre comuni origini non solo romane, ma “monteverdine” (dal nome di un quartiere romano non lontano dal Vaticano, “Monteverde Vecchio”), mi ha raccontato degli albori del nostro comune quartiere e della costruzione delle case intorno a via dei Quattro Venti, con piacevoli aneddoti della vita della sua famiglia, lì, negli anni 40 e 50, degli anni della scuola al Collegio Romano, e poi degli studi alla “Sapienza”, la prima università di Roma.

Maria Fidecaro, con il suo entusiasmo e la sua simpatia, ha contagiato anche le centinaia di migliaia di visitatori che ogni anno visitano il CERN. Maria e Giuseppe, infatti, figurano da protagonisti in uno dei filmati divulgativi del CERN, quello che viene proiettato all'interno della visita del Sincro-Ciclotrone, il primo acceleratore di particelle del “loro” laboratorio: l’acceleratore che li ha accolti al loro primo arrivo a Ginevra.

Quando si parla di Maria Fidecaro, a molti viene spontaneo parlare di Maria e Giuseppe Fidecaro. Chi, come me, li ha conosciuti negli anni della loro pensione, li ha visti, infatti, quasi sempre insieme. Maria Fidecaro era in pensione dal 1995, ma lei e suo marito continuavano a venire al CERN quasi ogni giorno, continuando a lavorare e a interessarsi delle nuove ricerche e dei nuovi studi. Arrivavano insieme, e insieme li si incontrava nei corridoi. E a tutti, sempre insieme, regalavano il loro sorriso gentile, rischiarando i corridoi del CERN.

C’è una frase — più che una frase, una definizione — che mi ha colpito e che voglio lasciarvi, perché penso che ben ritratti l’affabilità di Maria Fidecaro. L’ho sentita alla cerimonia funebre di venerdi scorso, alla quale ho partecipato. L'ha usata Ugo Amaldi, figlio di Edoardo, fisico e ricercatore anch’egli e grande amico di Maria Fidecaro fin dai tempi dell’università. Ugo Amaldi, in francese, ha ricordato all’assemblea di quando la sua amica Maria, di qualche anno più grande, spiegava a lui e ai suoi colleghi, ancora studenti, l’utilizzo di alcuni strumenti di laboratorio; e di come lo facesse, usando le esatte parole di Ugo Amaldi, “avec une patience souriante”; ovvero, con una “pazienza sorridente”.

In questo momento di tristezza, un pensiero va a Giuseppe, ai loro figli, ai loro nipoti e alla loro famiglia, ai quali porgo le mie più sentite condoglianze.

Gli occhi gentili e sorridenti di Maria resteranno per sempre nei miei ricordi. Occhi cortesi e luminosi, esattamente come quelli di suo marito Giuseppe; occhi rari, che donano un sorriso al solo incontrarli.

Buon riposo, Maria.

— Riccardo.

The smiling eyes of Maria Fidecaro

Two smiling, kind eyes closed last September 17; the bright and curious eyes of an Italian researcher who has been a protagonist and witness to the entire history of CERN. They are the eyes of Maria Fidecaro.

In the early 1950s, in her early twenties, Maria Cervasi finished her physics studies at “Sapienza” in Rome under Carlo Bernardini and then worked as an assistant in the same department, in the prestigious physics institute of Enrico Fermi and Edoardo Amaldi. And it was there, and then during their experiments on the summit of the Matterhorn to study cosmic rays, that she met her future husband, Giuseppe Fidecaro.

In 1954, Maria Cervasi and Giuseppe Fidecaro both moved to the University of Liverpool to continue their studies on the decay of unstable particles with different experimental techniques: Giuseppe with a grant from the newly formed CERN, Maria with a grant from the then “International Federation of University Women (IFUW),” now “Graduate Women International (GWI).” There is a nice 1955 photo of her at the “Nuclear Physics Research Laboratory” at the University of Liverpool with two of her colleagues, Alec Merrison (later to become Sir Alec) and Alan Wetherell.

In 1955, the engaged couple married; Maria Cervasi became Maria Fidecaro, and they continued their work as researchers in Liverpool. But come the summer of 1956, Maria and her husband Giuseppe left Liverpool and moved to Geneva to join the first group of scientists at CERN. At that time, the great European laboratory, founded only two years earlier, was still under construction. Work was progressing, but nothing was ready yet, so much so that the first researchers’ studios and offices were still housed in temporary buildings: at the Geneva Physics Institute and Villa Cointrin, as Maria Fidecaro often recalled in her interviews.

Maria and Giuseppe worked on the study and construction of the very first CERN experiments. Giuseppe Fidecaro recalled in a 2014 interview that the experiments of the time were significantly smaller than modern ones, and only very few people could work on them. Mary and Joseph were among them. And since then, they have continued to be part of the lab’s history.

The group in which Maria Fidecaro started working at CERN was also small, with only three people. They were working on the brand new particle accelerator on which Giuseppe was also working, the "Synchro-Cyclotron," and together, they designed a new system to get "polarized" proton beams; that is, beams of protons all showing one of their characteristics, which is called "spin", aligned in one direction. In her career, Maria Fidecaro worked in several other experiments at CERN on different accelerators. She studied the interactions between nucleons — the particles that make up the nucleus of all atoms: protons and neutrons. She also participated in the experiment called “WA78“ experiment, on the “Super-Proton-Synchrotron” (SPS) accelerator, which was dedicated to the production of particle-antiparticle pairs; and she worked on the precise measurement of the conservation of some base physical properties with the “CPLEAR” experiment. For several years, she led the "CPL" group within the "Particle Physics Experiments" division at CERN and helped start other experiments, such as the “NA48/2“ and “NA62” experiments. In the last years of her long career, moreover, as she herself mentioned on several occasions, she liked to review the results of her previous studies, to double-check them and see if she had missed anything, or if some other conclusions could be made on the basis of the old data.

Personally, I met Maria and Giuseppe Fidecaro in 2003, when I first came to CERN as a student to prepare my dissertation. Unfortunately, I never had the good fortune to work with them directly, but in all these years, we met each other in the corridors of CERN; or on the streetcars and buses that took us, all three of us, back to the city center in the evening; or at the services of the Italian church in Geneva. And in all these years, it was always a pleasure to meet and greet them and receive their greetings. A greeting that was always sincerely cordial and joyful, and each time accompanied by the cheerful look of those kind eyes.

Then, unfortunately, the outbreak of COVID-19 also interfered with the life of the lab, and for a long time, I did not meet them again. But about a year ago, at one of the celebratory meetings in CERN’s history, I had the joy of meeting them again. I had driven to work that day, so knowing that Mary and Joseph lived not far from where I lived, I offered them a ride. It was a very pleasant and enjoyable car ride: Maria had sat in the front seat and, having discovered our common origins, not only Roman, but “monteverdine” (from the name of a Roman neighborhood not far from the Vatican, “Monteverde Vecchio”), she told me about the beginnings of our neighborhood and the construction of the houses around one of its main streets, Via dei Quattro Venti, with pleasant anecdotes of her family’s life there in the 1940s and 1950s, her school years at Collegio Romano, and then her studies at “Sapienza,” Rome’s first university.

Maria Fidecaro, with her enthusiasm and friendliness, has also infected the hundreds of thousands of visitors who visit CERN every year. Maria and Giuseppe, in fact, appear as protagonists in one of CERN’s educational movies, the one at the Synchro-Cyclotron, the first particle accelerator in “their” laboratory, the same accelerator that welcomed them when they first arrived in Geneva.

When people talk about Maria Fidecaro, it comes naturally to many to talk about Maria and Giuseppe Fidecaro. Those like me, who knew them in their retirement years, saw them, in fact, almost always together. Maria Fidecaro had been retired since 1995, but she and her husband continued to come to CERN nearly every day, continuing to work and take an interest in new research and studies. They would arrive together, and together, you would meet them in the hallways. And to everyone, always together, they would give their kind smiles, brightening the corridors of CERN.

There is a phrase—more than a phrase, a definition—that struck me and that I want to leave to you because I think it portrays Maria Fidecaro’s affability very well. I heard it at the funeral ceremony last Friday from Ugo Amaldi, son of Edoardo, also a physicist and a researcher and a great friend of Maria Fidecaro since her university days. Ugo Amaldi, in French, reminded the assembly of when his friend Maria, a few years older, used to explain to him and his colleagues, who were still students, the use of some laboratory instruments and how she did it, using Ugo Amaldi’s exact words, “avec une patience souriante”; that is, with a “smiling patience.”

At this time of sadness, a thought goes out to Giuseppe, their children, grandchildren, and family, to whom I offer my deepest condolences.

Maria’s kind and smiling eyes will forever remain in my memories. Gracious and bright eyes, exactly like those of her husband Joseph; rare eyes that give a smile upon just meeting them.

Have a good rest, Maria.

— Riccardo.

Member discussion: